A fable about MLOps... and broken dreams

21 min readFor a while, I was considering presenting more often at conferences and meetups. I was postponing it for quite some time, but this summer, I thought, “No more!” and applied to be a speaker at the Moldova Developer Conference. And I was accepted with a talk about MLOps! I thought I’d make the talk a kind of fairytale/fable story with blackjack and easter eggs. Fast forward a few weeks ago, in the first half of November, I was presenting at the conference, and because not everyone could attend it, I also decided to make a blog post on the topic I was presenting.

Intro

This article is divided into two parts, The Story and The Takeaways. Let’s start with the story.

The fable about MLOps…

Note that all the characters in the story are fictional. So is the setting in which the story happens. They are not inspired by concrete people or organizations but rather distilled from my many experiences and a few industry stories. Alright, story time.

Act 1: We need a PoC to prove ML is a good investment

In an alternate reality, or maybe just another time and place, there was a company - Lupine Corp. Lupine Corp. is a logistics company with a very long history, dating back since the revolution. However, no one remembers which one, could be the French, or the Bolshevik. Like any respectable company, they have a set of values and principles they abide by. One of their core tenets is to be cost-efficient. The other one is - no unnecessary risks.

Lupine Corp. are also reputable for doing their due diligence. So they knew that before launching their ML initiative, they needed to have their prerequisites in place.

-

They made sure to know their success metrics, meaning they established some KPIs and a way to report and track those.

-

They also had their data easily accessible and discoverable, not just existing somewhere in their databases. They knew this would be very important for the data scientists they will hire.

-

Finally, the leadership knew that Data Science and ML are much more unpredictable than traditional software engineering, and they adjusted their expectations accordingly.

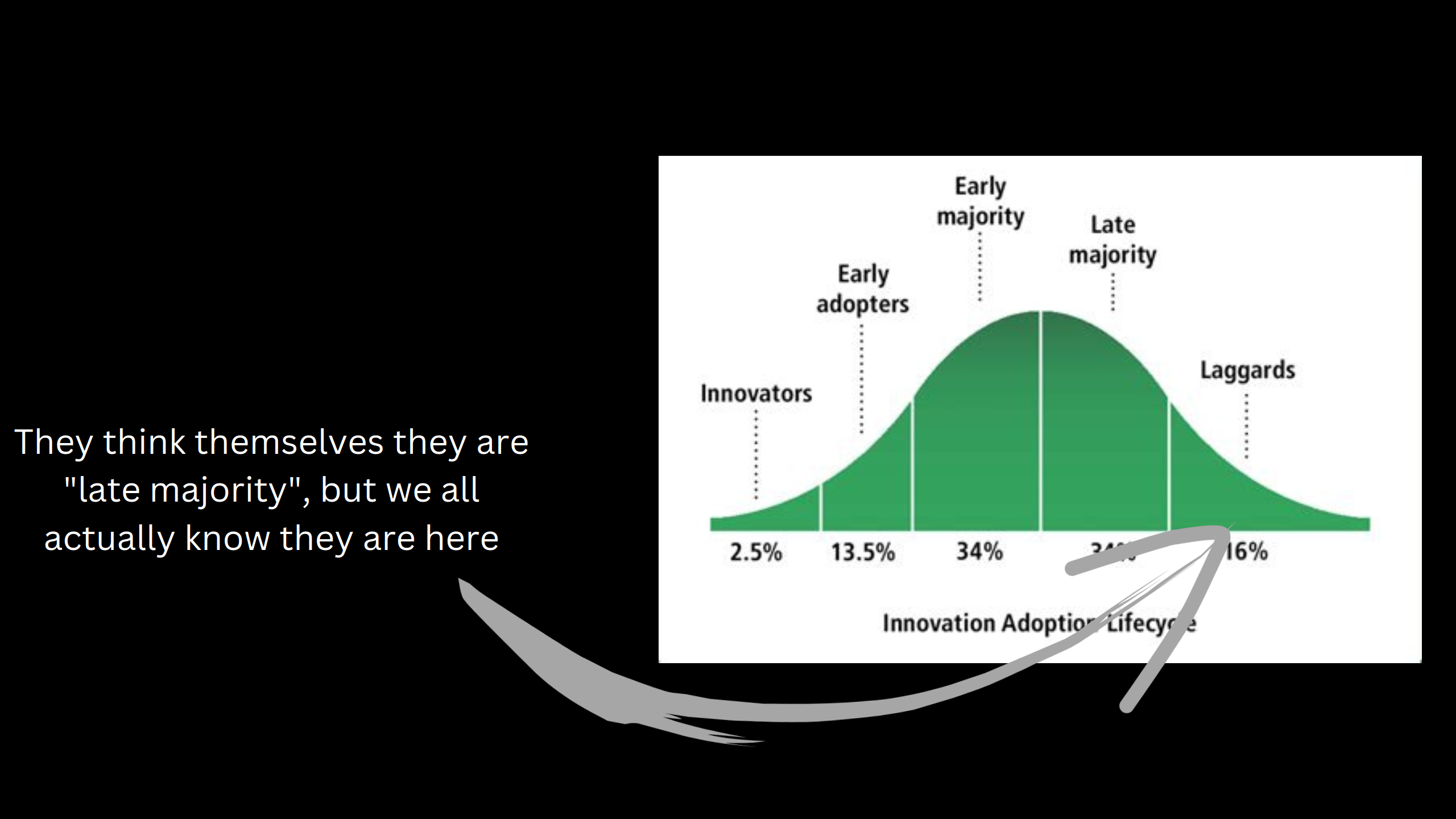

Side note: With only these 3 points, Lupine Corp. were so much better prepared for ML than the majority of the companies out there.

Lupine Corp. imposed some budget limitations because of the unpredictable nature of ML projects, so they only hired two people:

- Nifel Nifenson (image below, left), who previously worked for two years as a lone Data Scientist in a small company

- Nafaela Nafarri, PhD (image below, right), a Senior Data Scientist with six years of experience

Nifel Nifenson is a very results-oriented guy. One could say he’s the (rough) embodiment of the Lean Startup philosophy. Nafaela Nafari has a strong analytical mind. When Lupine Corp. asked them to deliver some results ASAP, they did just that and then some more. The results were very promising and done in record time. Senior management was ecstatic, and more use cases were in discussion.

Act 2: Expanding the team. Signs of trouble.

As all things in business and life, with larger scale, cracks became more apparent.

Nifel, Nafaela, and the new team members got along very well. It was a very nice team to work with. Everyone was professional and friendly. Yet somehow, the team’s velocity (as per Scrum, or “throughput” as per Kanban) wasn’t scaling as expected. It even started to go down after a few months. More people and more time were required to complete the same work Nifel and Nafaela had done a few months before. But why was this happening?

There are many reasons why. For example, many promising experiments couldn’t be replicated, even with all the notes the team took. Also, they observed increased complaints from some of the users of their deployed models. The first few weeks after the models were put in production, everyone was happy, but in time more and more bad feedback was received.

And if all that wasn’t enough, some of those productionized use cases started to receive a lot of traffic, sometimes up to two thousand concurrent users. They decided to horizontally scale their existing docker containers to serve them all. It wasn’t resource-efficient. It was hard to manage. And the latency SLAs were thrown out of the window with worrying regularity…

Act 3: Bringing the big guns

Lupine Corp. was upset with the prospect of their ML initiative imploding, so they hired Nuf Nufelman as the new Head of Data Science.

Previously he worked as a lead data scientist at a big non-FAANG company, similar in structure to Lupine Corp. but quite different culturally. His previous employer was basically a “throw money at the problem” type of company, and Nuf was shaped by this mentality too. Nuf was also a great DevOps believer.

He understood that the problem Nifel’s and Nafaela’s team faced was a replicability problem.

… and a retraining problem.

….. and a scalability problem.

They needed a well-structured process to research, develop, evaluate and productionize their work consistently.

In a meeting with the higher-ups, Nuf told them that if Lupine Corp. was serious about their ML intentions, they had to adopt MLOps, wholly and without question. They accepted.

To streamline adoption, Nuf suggested they don’t develop all the tools in-house but instead pay for an ML-platform-as-a-service (MLPaaS) by All-You-Need-And-A-Kitchen-Sink ($AYN). All-You-Need-And-A-Kitchen-Sink is a recently IPO-ed startup that “solves all the MLOps pains”.

Surprisingly, it worked.

Most of the past problems went away.

But a lot of the internal processes still needed adjustments. Because it was quite a generic tool, a lot of glue code had to be written. Also, people didn’t like using it. The learning curve was steep. And some of the API design choices and documentation could have been more pleasant to work with.

And did I mention the Enterprise tier was a-seed-investment-grant-per-month expensive? If you ever complain about AWS bills, this one was probably even worse, but I digress.

Act 4: Burning cash and its consequences

The ML and Data Science initiative continued to grow at Lupine Corp. They hired more people and sometimes heard more complaints about their ML platform. It was slightly annoying but not that important for the upper management. They had different pains.

How could they ever be content when this new MLPaaS gizmo was burning cash like crazy? And recall their main tenets. Increasing their operational efficiency was a recurring topic during their meetings.

But as anything in old, large corporations, it was a lot of talking and not so much doing.

And then, the earnings call day came…

Financials showed Lupine was burning a lot more cash than its competitors. They were no startup or scaleup. This was showing financial recklessness. Shareholders didn’t like it. Neither did the stock market. Their stock plummeted 20% in a week. Something between Meta and Netflix.

To alleviate the issue, Lupine Corp. decided to optimize its operations. Now for real.

They laid off many employees working on non-critical aspects of the business. Whether possible, they terminated said initiatives too.

It was clear one of the main reasons they were burning money was their ML platform. Obviously, the ML initiative was impacted. Nafaela and Nuf stayed, but Nifel was laid off. Layoff decisions were based on tenure and seniority.

Cutting costs worked. But it wasn’t a good long-term strategy, and Lupine Corp. knew this all too well. They needed to optimize their OpEx. So now, Lupine Corp. was looking for someone who could help. And they found someone. Someone,

Meet Nahum Nahreba.

He’s a platform engineer. He is known for thinking from first principles and building nimble, scalable solutions. He’s something of a Jeff Dean, although he might not be able to shift bits from one computer to the other. He helped scale a few startups. It wasn’t the first time he had to work on ML platforms.

TL;DR: He came. He saw. He solved the mess.

He persuaded Lupine Corp. to greenlight a major refactoring of the ML platform, pruning it of many unnecessary features, reducing the bill, and implementing a few features and tools internally, with a specific focus on developer experience and integration with the rest of the company’s infrastructure. It’s a fable, not a technical report, so I won’t dive deep into how he did it.

And so they lived relatively happily until Lupine Corp. management discovered IoT…

The end.

The takeaways

So, how could Lupine Corp. avoid this mess? And how can other companies like them avoid it too?

First things first, we need to give credit where credit’s due. This fictional company did a lot of stuff others don’t, so their success chances were already pretty high. They knew what success looked like for them, they had their data available and discoverable, and they had a correct mindset about this initiative. In my practice, most companies don’t have that.

I would argue one of the reasons Lupine Corp. had such fun hard times was a well-known quote:

“Premature optimization is the root of all evil” - Donald Knuth

… as cited by Nifel Nifelson, and most SWEs. Nifel, in this story, had somewhat more software engineering experience, and it was his responsibility to use an SWE mindset when starting their ML journey. He knew by heart the quote above, the KISS principle, and many others. But he also, like most of us, didn’t quite understand the nuances behind said quotes. Nifel treated MLOps as overengineering. Under management’s tight deadline and pressure to show good results and prove himself a specialist, he created good ML models but not-so-good ML systems.

By the way, the “fuller” quote sounds like this:

“We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.”

If only Nifel knew it like this… So the takeaway #1: Start early with MLOps.

Nifel’s (counter-)example shows we must consider adopting MLOps practices early on. But it’s not so simple either.

Software and data people are an enthusiastic bunch. We want to use many tools to solve many problems. We’re very prone to over-engineering. If we were rockstars, I think this tendency towards abuse would have manifested a bit differently. Thankfully we aren’t rockstars.

By the way, it’s not my first piece on picking tools, so you’d like to check out the other article about it.

When starting with MLOps, we can be overwhelmed by multiple tools, terms, concepts, and practices. We’ll hear from every corner how crucial it is to have pipeline orchestration, 17 types of ML and data tests, three types of observability, feature stores, model stores, metadata stores, stores to store stores… alright, I’m exaggerating now, but you got the idea.

You don’t need all this tooling, not from the start, even if it comes all bundled together, like AWS, GCP, or Azure offerings.

Using a fully-featured MLOps solution from the beginning usually doesn’t work.

Either because it’s too generic. And/or there are too many upfront costs. Also, it takes a lot of work to onboard your users.

Going head-first into MLOps is a bad idea for most of the same reasons.

What you do need in the beginning is to…

- quickly find and access your data

- seed that model training code

- record your experiment configuration

Then make sure to

- easily deploy your models

- have some tests

The rest will come after. All that said, the takeaway #2: Start small with MLOps.

Now onto more technical advice.

Simple data collection and discovery

Lupine Corp had this, but I’m sure you don’t. So, what should you do? First, you need to understand The Why? We’re past the Big Data hype by almost ten years. Organizations now have lots of data… but it takes a lot of work to use it properly. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that for the absolute majority of the projects I worked on, accessing datasets was my second most annoying problem. The first one was the lack of a baseline and success metrics. As I said, Lupine Corp. was in fact really good. Your company probably isn’t.

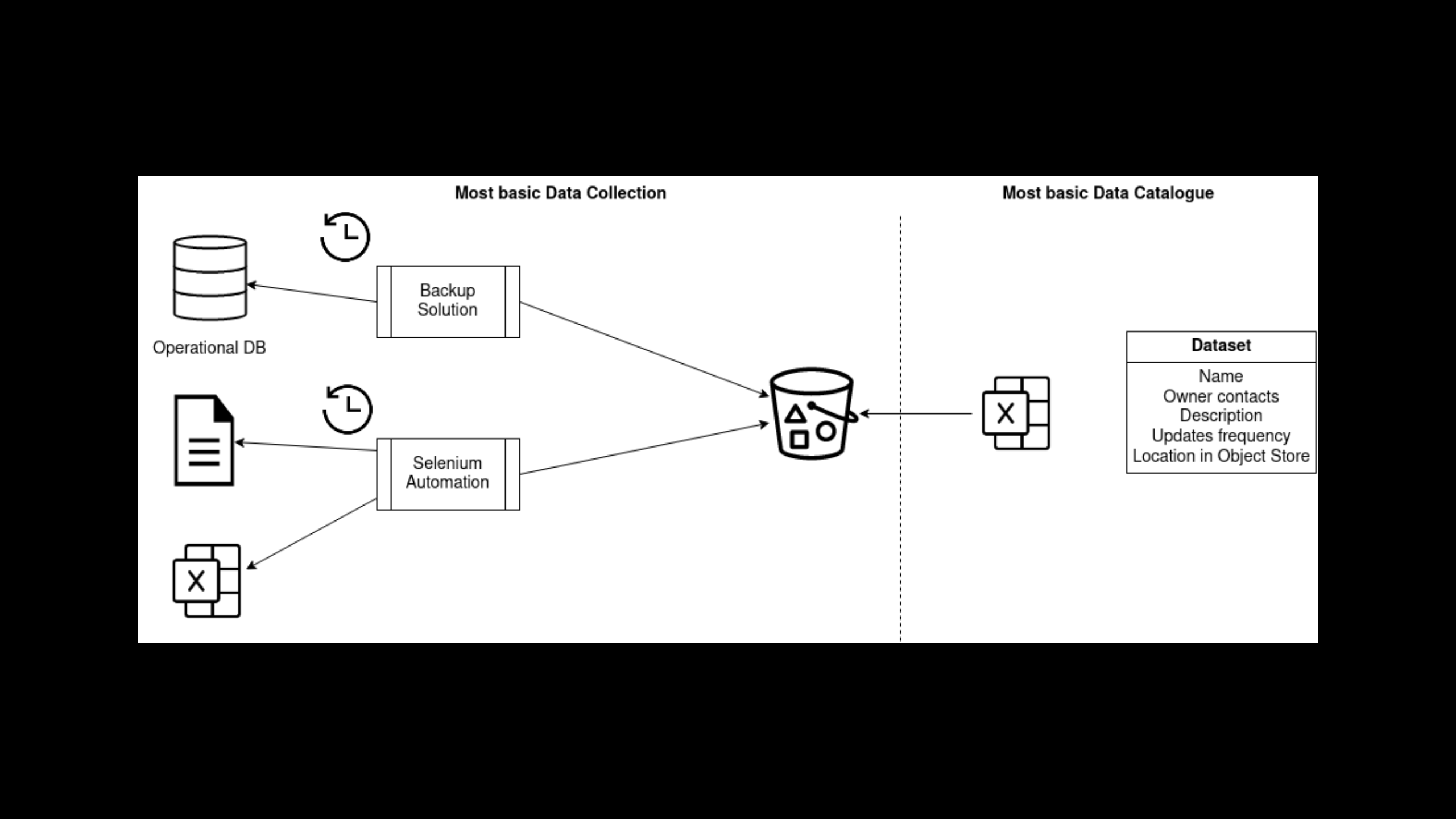

Alright, we know what “data collection” is. ETL pipelines and all that. Or a few scripts running as CRON jobs, dumping files into an S3 bucket. But what about data discovery?

A short googling session will reveal terms and technologies like data governance, data lineage, Amundsen from Lyft, Apache Atlas, Google Data Catalog… yeah, no. Not yet.

Have a shared spreadsheet. In it, each row is about a dataset. Name, short description, update frequency, contact person, and location in the object store. That’s it, at least in the beginning.

Do this, and your data scientists and ML engineers will be happy as hell. You’ll get recruits just by word of mouth.

Here’s a wacky architectural diagram for what you need for simple data collection and discovery.

Pro tip: when you dump your raw data into those buckets, don’t override your old data. You’ll see why later.

Replicable experiments

This one requires a few steps, but they’re relatively straightforward. First, you need to seed your pseudo-random number generators, aka PRNGs.

Not everyone knows this, or maybe not explicitly, but ML code is full of randomness. We need to initialize the parameters of our ML models - we use some random distributions. We also need to shuffle our data - also randomness. This is trivial for a machine learning practitioner. What is less trivial is how this randomness is “created”. You see, randomness in computers is not entirely random.

(Optional Paragraph) We use special algorithms, based on stuff like chaos theory, which given an initial state, or a seed, and a set of usually recurrent rules, will generate a sequence of values. The rules are fixed, so the algorithm is deterministic, but the values are chaotic, meaning there’s no discernable pattern. Now, the seed value, the initial state used in these PRNGs is usually a genuinely random number, it can be the exact current temperature of the CPU, the clock drift between multiple CPU cores, or some other value that is naturally random. But you can manually provide the initial state, and thus when running the same sequence of operations multiple times, get the same sequence of values.

Back to our business. We can seed, or manually provide the initial states for our PRNGs so that running the same code will give us the same results - same models, same performance.

This is super important because if we can get the same results, we can properly validate and compare ML models and pick the best ones.

Python ML code has multiple sources of randomness, which can, and should, be seeded. This is because most numerical libraries in Python are written in C/C++/Fortran, and Python is a convenient wrapper to access these routines.

But there are a few more things between you and numerically replicable experiments besides PRNGs.

cuDNN is also standing in the way. cuDNN is NVidia’s low-level set of primitives for deep learning. It has multiple GPU-optimized implementations for convolutions, pooling, linear layers, various activation functions, and so on. Now, cuDNN has a clever way of achieving maximum performance on different hardware for various scenarios. It tests multiple implementations of the same algorithm at the start of the program and picks the fastest one. This selection can be non-deterministic (read random). Why? I am not sure, but as far as I understood, its heuristics might behave differently if there’s anything else running on the GPU. To disable this behavior, one has to set the torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = False. To my knowledge, there are also a few other sources of randomness in cuDNN, and you can disable (some) these by setting torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True. And if you’re interested in finding out more on how to run replicable PyTorch experiments, check out this page from the docs. And if you’re not, search if there are similar behaviors in your favorite framework.

Finally, most of the time, ML algorithms will try to take advantage of modern multi-core CPUs, and when designing replicable experiments, one has to think about it too.

import random, os

import numpy as np

import torch

random.seed(seed)

np.random.seed(seed)

torch.manual_seed(seed)

torch.cuda.manual_seed(seed)

torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = False

def seed_worker(worker_id):

worker_seed = torch.initial_seed() % 2**32

np.random.seed(worker_seed)

random.seed(worker_seed)

g = torch.Generator()

g.manual_seed(0)

dl = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=batch_size, num_workers=num_workers,

worker_init_fn=seed_worker, generator=g)

Pro tip: when testing a machine learning model configuration, run it multiple times using different seed values. It will reduce the chance that you’re just lucky.

But to replicate experiments, one needs to know all their parameters, which brings us to the next part…

Experiment tracking

import mlflow

from mlflow.models.signature import infer_signature

with mlflow.start_run():

mlflow.log_param("batch_size", 32)

# Metrics can be updated throughout the run

mlflow.log_metric("accuracy", 0.973)

mlflow.log_metric("accuracy", 0.981)

with open("outputs/test.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("hello world!")

mlflow.log_artifacts("outputs")

model_signature = infer_signature(example_inputs, model.predict(example_inputs))

mlflow.sklearn.log_model(model, artifact_path="./sklearn-model",

registered_model_name="sklearn-rf-reg-model",

signature=model_signature)

Just try to track as much as possible. I do. And it helped me a great deal. If you are ok with managing your infra, use MLFlow. If you would rather pay for a good managed solution, Neptune.ai and Weights and Biases are very nice.

Pro tip 1: For maximum benefit, group similar algorithms together. It will make it easier to compare those with stuff like parallel coordinate plots.

Pro tip 2: Also, try to track and version all your data. Either with DVC or something else. That’s why you shouldn’t override the raw data in the buckets. Because if you do override it, you won’t be able to replicate the results of your experiments.

So you have a trained ML model. You can also fully replicate it. Now what?

ML Serving

You need to deploy and serve it somehow! How? Use docker and an app server! Consider Ray Serve, BentoML, or Seldon if you care about SLAs. These are specialized solutions that provide impactful features like adaptive batching, model pooling, and so on. If you care much about SLAs, try Triton Inference Server from NVidia. If you want to dive deeper into details, read my blog post on the topic.

ML Tests

What about tests? ML code is still code. So it needs tests. ML testing is a big and hairy problem. I promise I will eventually write some article about it, but for now, think about this problem like this:

You need to have two types of tests,

- Behavioral tests, which will measure predictions. These can become your regression suite, where you add various edge cases on which you don’t want to fail ever again

- Unit/Integration tests, which will measure training, serving, and preprocessing code correctness. Stuff like “The model should reduce its loss after one iteration” or “The shape of the output should be [x,y,z] given that the input shape was [x,m,n]” and so on. These will spot bugs in your implementation.

Depending on your application domain, here are a few links to help you with ML testing.

- Deepchecks library

- ML Model Testing: 4 Teams Share How They Test Their Models | Neptune.ai Blog

- Machine Learning in Production - Testing | ApplyingML

- Made With ML Testing Machine Learning Systems: Code, Data and Models

- Effective testing for machine learning systems | By Jeremy Jordan

CI/CD

If you have done everything until this point, having CI/CD should be easy. Kudos for triggering conditional steps for retraining if the training/model code changes. The conditional build behavior can be implemented with either something like dvc repro + some caching between runs or clever git diff manipulations.

# not the most production ready hack, but maybe it will help you

...

jobs:

check:

runs-on: ubuntu-20.04

outputs:

DIFFS: ${{ steps.diffs.outputs.DIFFS }}

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

fetch-depth: 0 # actually will need some adjustments

# fetch only as many as necessary: https://github.com/actions/checkout/issues/438

- name: Last good run commit

run: |

curl -s \

-H "Accept: application/vnd.github+json" \

-H "Authorization: token ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}" \

https://api.github.com/repos/{{ USER }}/{{ REPO_NAME }}/actions/workflows/training-trigger.yml/runs?status=success | jq \

-r ".workflow_runs[0].head_commit.id" > last_good_commit.txt

- name: Show and set DIFFS

id: diffs

run: |

DIFFS=$(git diff HEAD $(cat last_good_commit.txt) --name-only | tr '\n' ' ')

echo "::set-output name=DIFFS::$DIFFS"

echo $DIFFS

train:

needs: check

if: contains(needs.check.outputs.DIFFS, 'train.py')

uses: {{ USER }}/{{ REPO_NAME }}/.github/workflows/training.yml@master

One important thing to note is somewhat related to CI. ML projects tend to have a naturally tight relation between EDA, data processing, training, and serving code. As a result, I highly recommend designing ML projects as monorepos and adopting monorepo-related practices and patterns for building, versioning, and code compatibility.

Epilogue

All the advice above is focused on simplicity. You must understand that the solutions I suggest have a very clear scope. These are solutions you should only consider at the beginning of your MLOps journey.

Let me make it simpler with a table.

| Q | A |

|---|---|

| Is it going to scale? | Nope |

| Is it production-ready? | It’s PoC-ready |

| How quickly can I set it up? | A few days at most |

| Is it better than doing nothing? | Yes!!! |

| Is it cost-effective? | Hell yes |

| Is it more cost-effective than using a paid or even an existing OSS solution? | IMO much more so |

These recipes are Maximum ROI - Minimum Effort solutions to get you started. Eventually, you will discover that they don’t quite suit you. Only then switch to something else. You’ll make a better-informed decision then.

P.S.

I was serious about presenting more often at conferences and meetups. And that’s why I will also be presenting at the Belgium MLOps meetup on 5th December 2022. So if you’d like to learn about my MLOps adventures in setting up my research environment, please join us via this link.

P.P.S.

The story is based on the “Three Little Pigs” one in its Romanian/Russian variant, where the piglets are named Nif-Nif, Naf-Naf, Nuf-Nuf. Now, the local, russian-speaking population has a joke about the 4th piglet, which I’ll let you guess his name. Special kudos to those who also get the meaning/connotation of the fourth piglet.