How to Solve the Model Serving Component of the MLOps Stack

23 min readThis blog post was written by me and orginally posted on Neptune.ai Blog. Be sure to check them out. I like their blog posts about MLOps a lot.

Model serving and deployment is one of the pillars of the MLOps stack. In this article, I’ll dive into it and talk about what a basic, intermediate, and advanced setup for model serving look like.

Let’s start by covering some basics.

What is Model Serving?

Training a machine learning model may seem like a great accomplishment, but in practice, it’s not even halfway from delivering business value. For a machine learning initiative to succeed, we need to deploy that model and ensure it meets our performance and reliability requirements. You may say, “But I can just pack it into a Docker image and be done with it”. In some scenarios, that could indeed be enough. But most of the time, it won’t. When people talk about productionizing ML models, they use the term serving rather than simply deployment. So what does this mean?

To serve a model is to expose it to the real world and ensure it meets all your production requirements, aka your latency, accuracy, fault-tolerance, and throughput are all at the “business is happy” level. Just packaging a model into a Docker image is not “the solution” because you’re still left with how to run the model, scale the model, deploy new model updates, and so on. Don’t get me wrong, there’s a time and place for Flask-server-in-Docker-image style of serving; it’s just a limited tool for a limited number of use-cases, which I’ll outline later.

Now that we know what serving implies, let’s dive in.

Model Deployment scenarios

When deciding how to serve our ML models, we must ask ourselves a few questions. Answering these should help us shape our model serving architecture.

Is our model user-facing?

In other words, does the user trigger it through some action and need to see an effect dependent on our model outputs in real-time? If this sounds too abstract, how about an example? Are we creating an email autocomplete solution like the one in Gmail? Our user writes some text and expects a relevant completion. This kind of scenario needs an “interactive” deployment. This is probably the most common way to serve ML models. But it’s not the only way.

Suppose we don’t need the model’s predictions right away. We’re fine waiting even an hour or more to get what we need. How frequently do we need to get these predictions? Do we need something like a weekly excel report or tagging some inventory item descriptions once per day? If this sounds about right, we can run a “batch” process as a way to serve our model. This setup would probably be the easiest to maintain and scale. But there’s another, 3rd way.

Does the latency matter?

You don’t need to “respond” to the user but still must act based on the user’s action. Something like a fraud detection model that gets triggered on a user’s transaction. This scenario asks for a “streaming” setup. A scenario like this is usually deemed the most complex to handle. Although it would sound like the interactive setup would be harder to build, streaming is generally harder to reason about and thus harder to implement properly.

Let’s dive into the details of each of these setups, the best time to use them, and the trade-offs.

Model Deployment setups

We should consider a few general “setups” based on our business needs when it comes to exposing ML models to the outside world for consumption.

Batch model serving

This one is the easiest to implement and operate of all possible setups. Batch processes are not interactive, i.e., they do not wait for some interaction with another user or process. They just run, start to finish. Because of this, there are mostly no latency requirements; all it needs is to be able to scale to large dataset sizes.

Because of this latency insensitiveness, you can use complex models – Kaggle-like ensembles, huge gradient boosted trees or neural networks, anything goes, because it is expected that these operations won’t be done in milliseconds anyway. To handle even multi-hundred GB datasets, all you need is something like CRON, a workstation/a relatively capable cloud VM, and to know how to develop out-of-core data processing scripts. Don’t believe me? Here’s an example to prove my point.

It becomes a bit more challenging if you need to handle TBs of data. You will need to deal with multi-node Apache Spark, Apache Airflow, or something like it. You’ll have to think about potential node failure and how to maximize the resource utilization of said nodes.

Finally, if you’re operating at Google-size datasets, check this link. Operating at such a scale brings issues like “chatty neighbors”, straggling tasks/jobs, “thundering herds”, and timezones. Yeah, and congratulations on your gargantuan scale.

Streaming model serving

As we already mentioned, batch processes are not the only ones that don’t need to wait on user interaction, i.e., they are not interactive. We can also have our models act on streams of data. These scenarios are much more latency-sensitive than batch processes.

Standard tools for streaming model serving are Apache Kafka, Apache Flink, and Akka. But if you need to operate your model as a streaming/event-driven infrastructure component, these are not your only options. You can create a component that will be a consumer of events on one side and a producer on the other. Whatever you do, be mindful of back pressure. Streaming setups care a lot about being able to process large volumes of continuously flowing data, so be sure to not make your deployed ML models the bottleneck of this setup.

Another thing to consider when developing streaming ML serving solutions is model serialization. Most streaming event processing systems are JVM-based, either Java or Scala native. As a result, you will likely discover that your model structure is limited by the capabilities of your serializer. For a story about how model serialization can become an issue, check out this article’s sub-section – the resulting models can be tedious to deploy.

Here are some useful links regarding the same –

- Deploying ML Models in Distributed Real-time Data Streaming Applications | TDS

- Using Akka for leveraging speculative execution in model serving

- Automated model refresh with streaming data

Interactive model serving (via REST/gRPC)

The most popular way to serve ML models – using a server! In fact, a lot of people, when discussing ML serving, refer to this specific setup rather than any of the three. An interactive setup means the user somehow triggers a model and is waiting for the output or something caused by the output. Basically, it’s a request-response interaction pattern.

There are many ways to serve ML models in this setup. From a Flask or FastAPI server with an in-memory loaded ML model to specialized solutions like TF Serving or NVIDIA Triton, and anything in between. In this article, we will mainly focus on this setup.

I’ve seen people developing batch solutions where the ML component is actually a server being called by said batch program. Or components in a streaming event processing system calling HTTP servers that serve ML models. Being a flexible, reasonably simple to reason about, and well-documented approach, many are “abusing” the interactive pattern.

Note on Cloud, Edge and Client-side serving

What if we are developing a mobile app and want our ML-enabled features to work without the internet? What if we want to provide our users with magical responsiveness? To make waiting for a response on a web page a thing of the past. Enter client-side serving and serving ML on edge.

Things to consider

When designing ML systems, we need to be aware of this possibility and the challenges of such a deployment scenario.

- Deployment on browser clients is straightforward using TF.js. ONNX can also be an option, albeit a bit more complicated.

- As for mobile, we have multiple variants, including CoreML from Apple, TFLite from Google, and ONNX.

- For edge devices, depending on their compute performance, we can either run ML models just like we’d do in the cloud or create custom TinyML solutions.

Notice that, in theory, browsers and smartphones are edge devices. In practice, they are treated differently because of the wildly different programming models. More often than not, edge servers are classic computers, either running on ARM or x86 hardware, with traditional OSs, just much closer to the user, network-wise. Mobile devices need to be programmed differently because of the big difference between mobile and more common OSs. More recently, mobile devices have specialized DSPs or co-processors optimized for AI inference.

Browsers are even more different because browser code is usually architected around the idea of a sandboxed environment and the event loop. More recently, we have web workers, which make the creation of multi-process applications easier. Also, when serving an ML model in a browser, we can’t make any assumptions about the hardware on which the model will run, resulting in a potentially horrible user experience. It can very much be that a user opened our web app with the ML model on a low-end mobile device. Only imagine the lags that site will have.

Trade-offs

There could be multiple reasons to move ML serving closer to the edge. Usual motives are latency sensitiveness, bandwidth control, privacy concerns, and the capability to work offline. Keep in mind that we can have various hierarchical deployment targets, spanning between the user’s client device to an IoT hub or router closest to the user, to a city or region-wide data center.

Deploying on edge devices or client devices usually trades off model size and performance for reduced network latency or the possibility of dramatically reducing the bandwidth. For example, deploying a model for automatic face recognition and classification on a mobile phone maybe isn’t such a good idea, but a tiny and simple one that can detect whether there’s a face in the scene or not is. The same goes for an automatic email response generator vs. an autocomplete keyboard model. The former usually isn’t needed on-device, while the latter must be deployed on-device.

In practice, it is possible to mix edge/on-device models with a cloud-deployed model for maximum predictive performance when online, but with the possibility to retain some AI-enabled features offline. This can mostly be done by writing custom code, but it is also possible to use something like Sedna for KubeEdge if your edge devices are capable of running KubeEdge.

A real-world use-case

A common but less discussed scenario for deploying on edge – A retailer wants to use video analytics in their grocery stores. They developed a suite of powerful computer vision models to analyze the video feed from their in-store cameras and were met with a hard constraint. The internet provider couldn’t ensure the upload latency, and bandwidth from their locations couldn’t support multiple streaming video feeds. The solution? They bought a gaming PC per store, put it in the staff room, and did their video analysis locally without needing to stream videos from the stores. Yes, this is an edge ML scenario. Edge computing is not only about IoT.

Serving ML models the right way

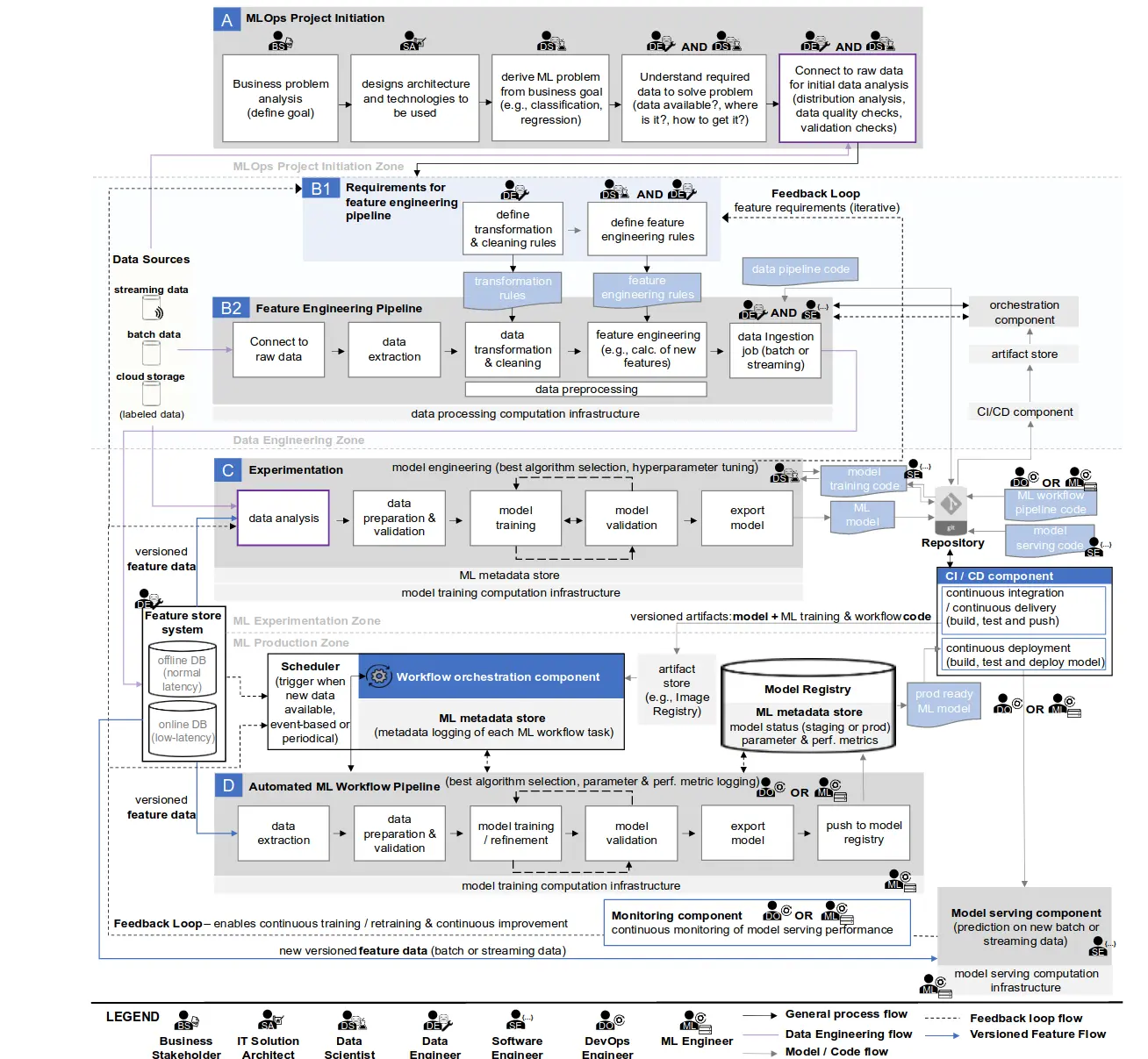

Model serving has a tight relationship with metadata stores, ML model registries, monitoring components, and feature stores. That is quite a lot. Plus, depending on concrete organizational requirements, model serving might have to be integrated with CI/CD tooling. It might be necessary to either ensure a staging environment to test newly trained models or even continuously deploy to production environments, most likely as a shadow or canary deployment.

What makes a deployment good?

Keep in mind that a good model serving solution isn’t only about cost-efficiency and latencies but also about how well it is integrated with the rest of the stack. If we have a high-performance server that is a nightmare to integrate with our observability, feature stores, and model registries, we have a terrible model serving component.

A common way to implement the whole model deployment/serving workflow is to have the model serving component fetch concrete models based on the information from the ML model registry and/or metadata store.

For example, using a tool like Neptune.ai, we can track multiple experiments. At some point, if we decide we have a good candidate model, we tag it as a model ready for staging/canary. Remember, we’re still interacting with Neptune.ai, no need to use any other tool. Our ML serving component periodically checks in with the ML model registry, and if there’s a new model with the compatible tag, it will update the deployment like this. This method allows for more accessible model updates without triggering image builds or other expensive and complex workflows. An alternative approach is to redeploy a pre-built serving component and only change its configuration to fetch a newer model, something like this. This approach is more common in cloud-native (Kubernetes) serving solutions.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, frequently, the model serving component has to interact with feature stores. To interact with feature stores, we need to be able to serve not just serialized ML models but also have support for custom IO-enabled components. In some cases, this can be a nightmare. A workaround is integrating the feature stores at the application-server level and not at the ML serving component level.

Finally, we also need to log and monitor our deployed ML models. Many custom solutions integrate with tools like the ELK stack for logs, OpenTelemetry for traces, and Prometheus for metrics. ML does bring some specific challenges, though.

For a dive into what a good observability setup consists of, be sure to check out another blog post of mine.

First, we need to be able to collect new data for our datasets. This is mostly done either through custom infrastructure or ELK. Then, we need to be able to track ML-specific signals, like distribution shifts for input values and outputs. This is a highly un-optimized scenario for tools like Prometheus. To better understand these challenges, check out this blog post. A few tools try to help with this, most prominently WhyLabs and Arize.

What do we really care about?

Other than the usual suspects - tail latencies, number of requests per second, and application error rate, it is advisable to also track model performance. And here’s the tricky part. It’s rarely possible to obtain ground-truth labels in real-time or with a short delay. If the delay is significant, it will take longer to identify issues impacting our users’ experience.

Because of this, tracking the inputs and outputs distribution and triggering some action if these diverge significantly from what the model is expecting is pretty common. While this is useful, it doesn’t quite help track our predictive performance SLO (service-level objective).

The problem of tracking performance

Let me explain, on one hand, we can reasonably assume that divergences in our inputs and outputs distributions can result in degraded performance, but on the other hand, we don’t actually know the exact relation between the two.

We can have scenarios where a distribution for a feature drifts a lot from the expected distribution but has no significant impact on our ML model performance. We will have a false alarm in this case. But these relations change over time. So next time, when the same feature drifts again, it can result in a significant loss of predictive power of our ML models. As you can imagine, this is a nightmare to manage. So what can be done?

The solution – detection and mitigation

We deploy and update ML models to better our business. Ideally, we must “link” our model SLOs with business metrics. For example, if we notice that the ratio of users clicking on our recommendation drops, we know we are not doing well. For a text auto-correction solution, a similar business-derived model SLO could be the ratio of accepted suggestions. If it falls below some threshold, maybe our model is no better than the previous one. Regretfully this isn’t always this easy to do.

Because this problem can be so hairy, we usually extract ML model performance monitoring into a separate component and only track the system-level metrics, traces, and logs at the ML serving component level. We hope that as the infrastructure for ML model monitoring becomes better, ML serving components will provide significantly better integrations with these tools to make the troubleshooting of deployed models significantly easier.

Evolving model serving

Because the interactive serving setup is the most popular way to productionize ML models, we will discuss what a basic, intermediate and advanced setup looks like. What differentiates a good setup from a mediocre one is cost-effectiveness, scalability, and latency profile. Of course, the integration with the rest of the MLOps stack is also important. In general, deciding on what architecture and tools to use is always a tricky affair, with numerous trade-offs. If you’re interested in advancing your decision-making when it comes to making technical decisions, be sure to check out this article on what questions should you ask and some of the trade-offs you should expect. Don’t mind that it’s about programming languages, most questions apply to tools and frameworks too.

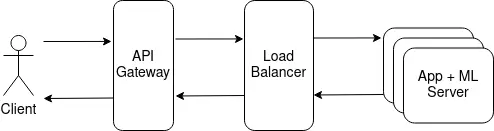

Basic setup

Recall, at the beginning of the article, I mentioned that there’s a time and place for an ML-model-in-Flask-server-in-a-Docker-container style of serving. A lot was said about this kind of serving, so I won’t dive into much detail. Note that the ML model can be either backed in the container or attached as a volume. If you are only creating a demo API or know for a fact that you won’t have much traffic (maybe it’s an internal application, which only 3-5 people will use), this can be an acceptable solution.

Or, if you can provision multiple very capable cloud VMs with powerful GPUs and CPUs and don’t bother having poor resource utilization and sub-optimal tail latencies, then it can also work. I mean, Facebook is doing very few tests for their software and still manages to be a huge tech corporation, so it may not always make sense to follow all software engineering best practices. Pros

- This setup has the advantage of being very easy to implement and relatively scalable (need to handle more requests => run multiple replicas). Cons

- The biggest issue is poor resource utilization because models are triggered on each request for a single input entry, and the web servers don’t need the same hardware as ML models.

- Then, there’s a huge lack of control over tail latencies, meaning you can’t enforce almost any SLO with this setup. The only hope to somewhat control your tail latencies is a good load balancer and enough powerful machines to run multiple replicas of your ML serving component.

To improve this setup, we must move onto a medium-level configuration.

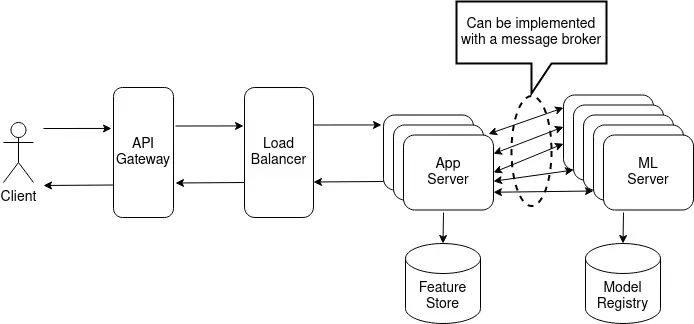

Intermediate setup

As mentioned above, we need to split the ML inference from the application server component to optimize the resource utilization and have better control over our latencies. One way to do it is using a publisher-subscriber asynchronous communication pattern, implemented with ZeroMQ or even Redis, for example.

So, after this “schism”, we can do a lot of cool tricks to perfect our serving component into an advanced one.

-

First, we can enforce much more granular and fine-tuned timeouts and retries. With such a setup, it is possible to scale the ML servers independently from the application servers.

-

Then, the most fantastic hack for this is to do adaptive batching. In fact, it’s such a great technique that it would make a solution almost advanced-level, performance-wise.

A good model serving solution isn’t just about how good is the server performance but also how easy it is to integrate the rest of the ML sub-systems. A machine learning serving component would need to provide at least some model management capabilities to easily update model versions without needing to rebuild the whole thing. For this kind of setup, the ML/MLOps team can design their ML workers to periodically check in with the model registry and, if there are any updates, fetch new models, something like this or this.

I am sure you noticed that the moderate setup is considerably more complex than the basic one. This complexity brings major downsides to this approach. At this stage, one needs some form of container orchestration, usually K8s, and at least some system observability, for example, with Prometheus and ELK.

Advanced setup

To be fair, a medium-level setup is enough for most ML serving scenarios. You shouldn’t consider the advanced ML serving setup as a necessary evolution of the last setup. The advanced setup is more like “heavy artillery”, which is required only in exceptional cases.

With all the bells and whistles proposed in the solution above, a question arises – “Why did we bother so much with all these tricks if there are pre-made solutions?”. And indeed, why? The answer would usually be – they needed something custom for their setup.

Specialized solutions like NVIDIA Triton, Tensorflow Serving, or TorchServe have solid selling points and pretty weak ones too.

Pros

- First, these serving solutions are very well optimized and usually perform better than a “medium + bells and whistles” solution.

- Second, these solutions are straightforward to deploy; most provide a docker container or a Helm chart.

- Finally, these solutions usually contain relatively basic support for model management and A/B testing.

Cons

- Now the downsides. The biggest one is the awkward integration with the rest of the MLOps ecosystem.

- Second, related to the first, these solutions are hard to extend. The most convenient way to solve both these is to create custom application servers that act as proxies/decorators/adapters for the high-performing pre-built ML servers.

- Thirdly, and this is probably a thing that I personally don’t like, is that these solutions are very constraining in terms of what models can be deployed. I want to keep my options open, and having a serving solution that accepts only TF SavedModels, or ONNX-serialized isn’t aligned with my values. And yes, even ONNX can be limiting, for example, when you have a custom model (see the subsection – the resulting models can be tedious to deploy) which uses operations yet unsupported by ONNX.

As you might have already guessed, I don’t use these solutions for the most part. I prefer PyTorch, so TF Serving is a no-go for me. Note, it’s just my context. If you use TF, consider using TF Serving. I tried it a few years ago for a TF project. It’s pretty good for serving, but a bit cumbersome for model management, if you ask me.

I said I use PyTorch primarily, so maybe TorchServe? To be frank, I haven’t even tried it. Seems good, but I’m afraid it has the same model management issues as TF Serving. What about Triton? I can speak of its older incarnation, TensorRT Inference Server. It was a nightmare to configure and then discover that because of a custom model head, it couldn’t be served properly. Plus model quantization issues, plus the same woes of model version management as the previous two candidates… To be fair, I’ve heard it got better, but I still am very skeptical of it. So, unless I know my model architecture is unchanged and I need maximum possible performance, I will not use it.

To summarize, specialized solutions like NVIDIA Triton or Tensorflow Serving are powerful tools, but if you opt to use them, you better have serious performance needs. Otherwise, I would advise against it. But that’s not all –

-

Even if these solutions are feature-rich and performant, they still need extensive supporting infrastructure. Such servers are best suited as ML workers, so you still need application servers. To have a truly advanced ML serving component, you need to consider tight integration with your other systems and ML and data observability, custom-built or using services like Arize and Montecarlo.

-

Also, you need to be able to perform advanced traffic management. The systems mentioned above provide some limited support for A/B testing. Still, in practice, you would have to implement it differently, either at the application server level, for more fine-grained control, or at the infrastructure level, with tools like Istio. You usually need to be able to support gradual rollouts of new models, canary deployments, and traffic shadowing. No existing pre-built serving system provides all these traffic patterns. If you want to support these, be ready to get your hands, and whiteboards, dirty.

Note on cloud offerings

TL;DR: Cloud offerings give you “full-lifecycle” solutions, meaning that the model serving is integrated with solutions for dataset management, training, hyperparameter tuning, monitoring, and model registries.

Cloud offerings try to give you the simplicity of the basic setup, with the feature-richness of the advanced setup and the performance of the moderate one. For most of us, this is a fantastic deal.

Common differentiators for cloud offerings are serverless and autoscaled inference, with GPUs and/or special chips support.

-

Take Vertex AI from Google, for example. They provide you with a full MLOps experience and relatively easy model deployment, which can be served either as a cloud function or an autoscaled container, or even as a batch job. And because it’s Google, they have TPUs, which come in handy for really large-scale deployments.

-

Or, with an even more complete solution, take AWS. Their SageMaker, just like Vertex AI, helps you along the whole MLOps lifecycle. Still, it also adds a simple and cost-efficient way to run models for inference with Elastic Inference accelerators, which seem to be fractional GPUs, possibly via NVIDIA’s Ampere-generation MIGs, or using a custom chip called Inferentia. Even better, SageMaker allows for post-training model optimizations for target hardware.

Yet neither offers adaptive batching, some form of speculative execution/request hedging, or other advanced techniques. Depending on your SLOs, you might still need to use systems like NVIDIA Triton or develop in-house solutions.

Conclusion

Running ML in production can be a daunting task. To truly master this, one has to optimize for many objectives – cost-efficiency, latency, throughput, and maintainability, to name a few. If there’s something you should get from this article, then let it be these three ideas –

- Have a clear objective and priorities when serving your ML model

- Let the business requirements and constraints drive your ML serving component architecture, not the other way around.

- Think of the model serving as a component in the broader MLOps stack. Armed with these ideas, you should be able to filter subpar ML serving solutions from the good ones, thus maximizing the impact for your organization. But don’t make the mistake of trying to get everything right from the beginning. Start serving early, iterate on your solution, and let the knowledge from this article help you make your first few iterations somewhat better. Better to deploy something mediocre than not to deploy anything.